Blog

PlaceCal: The Story So Far

Creating a low social capital social network for Manchester.

I’ve spent the last 9 months working with PHASE@MMU, Smart City project CityVerve, and Manchester City Council to deliver PlaceCal, a crowd-sourced community events calendar. It’s been an extremely busy time with a lot of learning in a very short amount of time, and as we head into Phase 2 of our development I thought it’d be a good time to recap the process so far.

To start at the end: here’s a little clip from our launch party on 1st Dec 2017, where we organised the Winter Lights Switch-on in Hulme Park. Confused what Christmas lights and children’s choirs could possibly have to do with a smart city project? Find out more in the video…

Where it all began: Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods

Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods (MAFN) was a project centred around four resident-led neighbourhood partnerships in different areas of Manchester, led by the PHASE consultancy at Manchester School of Architecture. It’s part of Age Friendly Manchester, itself part of the World Heath Organisation’s Age Friendly Cities program. PHASE stands for “Place, Health, Architecture, Space and Environment”, which hints at the range of perspectives used in the project: we will return to this later.

MAFN set up four resident-led age-friendly partnerships in different areas of Manchester in 2015. These partnerships aim bring people together from diverse organisations such as public health providers, emergency services, housing associations, community organisations, residents’ associations, local councils and neighbourhood teams. The partnerships are designed to help tackle issues in each area by enabling residents and organisations to work together to identify problems, and then research, design, produce and evaluate solutions together. Resident-led is the key term here. Rather than a top-down approach where the remit of the work to be done is decided in advance, this kind of partnership allows people who live in an area to decide what the important issues are and get access to regional providers who might be able to fix those problems.

This is methodology is called asset-based community development or ABCD: aiding the people, resources and organisations (collectively “assets”) in an area to overcome common problems together, rather than imposing interventions from without. The partnerships can fund both their own projects and ideas submitted to them, help evaluate and support those projects, and create and direct strategy to address lacks. The board meetings give a physical interface to anyone or any organisation wanting to get involved in making the neighbourhoods more age friendly, drastically reducing the friction especially large providers usually face when trying to get involved in grass roots action. Throughout this whole process, the partnership can access the skills and support of the university. By the end of the intervention, the idea is for the partnerships to be self-sustaining, like MAFN’s Old Moat pilot. Some example partnership meetings from our reports are shown below.

Before continuing, it’s worth noting how hard it can be to write up this kind of work. What “the partnership” is or means to anyone at any given moment can be extremely hard (and often undesirable) to pin down. Decentralised resident-led groups, like most things in society, are complex structures that we believe offer the only real possibility for genuine change: however in doing so they make it extremely hard to write about exactly who did what when without making it sound like credit is being taken for the actions of a wider group. Therefore: when the rest of this article refers to “the partnership” or “we” it is referring specifically to me (Kim Foale), the Hulme Age Friendly Board, and PHASE@MMU working together to create PlaceCal and its requisite theoretical background. If anyone has any ideas how to resolve this issue with language, we are all ears!

This process is designed to combat the widespread “silos” that exist across all sectors. Silos occur when local councils, housing associations, or universities for example act alone over long periods of time. Each institution ends up with its own strengths and weaknesses, and inevitably creates parallel and disconnected knowledges, skills, facilities, and funding streams. If you’ve ever been involved in a community group and wondered “why can’t we just book a room on the local campus?” or “how come the same organisations seem to get all the funding?” or as a researcher wondered “how come it’s so hard to work with local organisations and get citizen involvement?”, then you’ve probably encountered this first-hand. Resident-led partnerships’ direct aim is to de-silo and allow cross-agency work, producing interventions that enable community wellness by solving problems at the root level.

For example. When we looked at the spatial data, one part of Hulme had some of the poorest self-reported health in the area, the lowest rate of car ownership and no bus service within 800m. Interviews with residents revealed that getting to the local health centre required a bus into and then out of town to go a very short overall distance. Even if everyone was given a bus pass, basic access to hospitals, health clinics, activities and supermarkets was extremely poor.

It had been long suggested by residents and councillors that a health visitor could use the church hall in the area to do a weekly surgery: a common solution in disconnected areas. However, it was reported that the NHS were unable to use the hall due to the lack of a disabled toilet. So we reach an impasse. Residents and councillors wanted a disabled toilet in the church, but due to siloed funding streams had no access to the skills or funding needed to make this happen. The church hall was willing to make the alternations, and equally didn’t have the funding to build it, and needless to say the NHS’s remit doesn’t exactly cover building work in community venues.

This was one of the first issues tackled by the partnership. By identifying the problem together, making it a shared neighbourhood objective, and allocating funds from the partnership budget, we were were able to enable the architecture school, health authority and church to work together. Over a few months we were successfully able to create an accessible toilet in the church hall.

This story is a great example of how the things that prevent community wellness are often relatively cheap and easy to implement, once the problem has been successfully identified — and that often, these needs are ongoing problems residents or organisations have been dealing with for a long time. The local knowledge of residents could not be realistically divined solely by any quantity of top-down measurement or data-gathering process: people are experts in their local area and had clearly identified the problem for a long time.

This brings us back to the role of the architect in partnership work. Architects are commonly seen as people who simply design buildings. In this case, building a disabled toilet is something a second year undergraduate student or a decent plumber could do: and of course, someone does have to design the thing. The much harder work lies in identifying the problem using the available data: starting from analysing maps of bus routes and public health data, through talking to residents to find the reason for the problems, to creating the conditions to make the change itself.

At the time of writing, the NHS are still waiting to start doing surgeries there, such is the planning time on these things. However, Manchester City Council are already using the church hall for a new programme of health and fitness activities. Two people with physical disabilities who used to go to the food bank are now staying for the lunch club which is hosted afterwards — previously they got their food and left. And of course, the partnership now has access to a versatile and accessible venue that meets everyone’s needs in the area.

By fixing this kind of problem at a root level, the eventual outputs can be very cheap to implement compared to any solution a single agency would devise, especially when considering total costs across multiple agencies. In fact, as anyone who has done enough community work knows, the main resource in this kind of situation can be time spent in meetings! In this case, compare the cost and maintenance of fitting a new toilet, as opposed to providing free bus passes or taxis and the health costs of an older population with no access to exercise facilities. This is a great example of how fixing an ongoing and hard-to-address issue has already begun to create neighbourhood wellness — in this case, filling a void in community provision that improves neighbourhood capability— rather than a symptom-based approach that would have tackled only the issues arising from the lack of suitable spaces.

So how does this connect to PlaceCal? We’re getting there…

“There’s nothing to do!”

The research methodology for the MAFN process involved a series of research activities such as walking interviews, focus groups, interviews, surveys, mapping workshops, and secondary data search. The explicit goal of this process was to involve the partnership and other providers in coming to an actionable shared understanding and consciousness of their area. We’re producing an action plan for each area detailing these findings (an old draft for Hulme is on the area blog): stay tuned for updates.

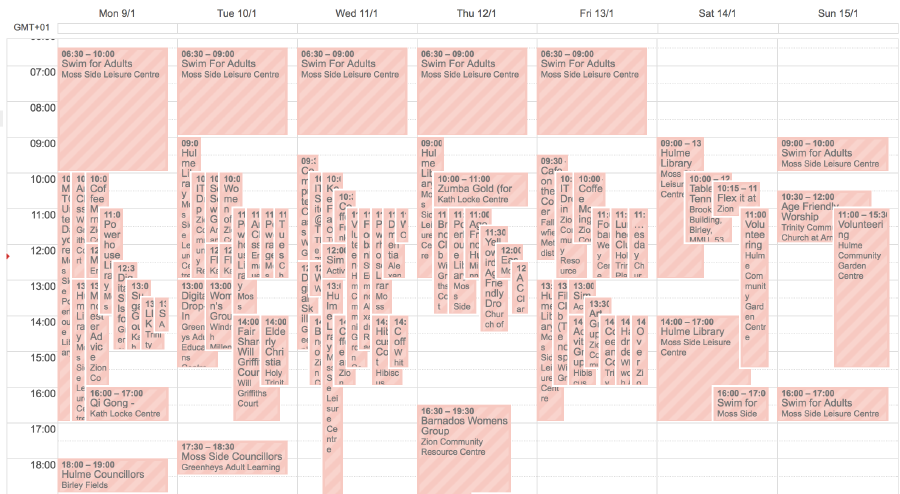

One of the first, extremely stark findings in this process was that older people didn’t think there was anything to do near them. So we set out to find out what there was to do. This single observation ended up being the entire design principle for the project. Through partnership meetings and hundreds of phonecalls, chats and emails, we asked everyone what events they knew about or were putting on, and if there’s anyone else we should talk to. Pretty soon each area had a Google Calendar a bit like this one:

These calendars were managed by the MAFN team, and were printed out and distributed at each Age Friendly board meeting; in fact, we’re still doing this. None of us quite realised how much there was going on in each area, or quite how many spaces people were using for events. We found that there were several age-friendly events almost every day for people to go to. We found that many major providers didn’t publish their data online or published a highly incomplete data set, usually managing some mass of leaflets and flyers, circulated and collated by the organisations themselves and a range of health providers and active citizens. Contrary to our initial assumptions there was a surplus of community spaces not a lack: however, most of these spaces were hidden and hard to find out about and access without a real-world local connection.

Very quickly we realised that these Google Calendars were going to be very difficult to maintain. Google Calendar is really not very good at browsing lots of events at the same time (OK, I did set the screenshot to week view for dramatic effect), and you’d either need to receive a printed copy by hand or be an active Google Calendar user to get the event information. It’s hard to see where events are at a glance or without clicking further, which turned out to be one of the most important factors in people choosing events. Most of all, it’s very clunky and not really designed for this task: it’s designed to manage a personal agenda, not a regional listing service.

More concerning than these issues though, it requires constant updates and maintenance by the team. This is a bottleneck for several reasons.

- It placed a high degree of expectation on initial contact with organisations. Anything missing after an initial meeting would require sending a change by email or a chance conversation. As most organisations were struggling to do any event promotion at all, and the event promoters themselves might not be using the Age Friendly calendar we were printing, it wasn’t viable to expect anything to stay updated after initial contact.

- We later discovered when we let organisations update their own calendars, in some cases they listed twice as many events as they did in what we thought was a comprehensive face-to-face interview. In other words, even people managing event spaces didn’t know everything that was happening in that space.

- Having a single point of ownership means a single point of failure. As soon as our funding ends, there is no obvious resource to maintain the calendar information unless a resident steps in to take over, which experience has shown is a big ask. Any sustainable system needs to be tolerant to funded roles and motivated community development workers coming and going, and allow organisations to manage their own data. Distributed ownership was therefore a prerequisite for a sustainable system.

- The job of maintaining the events scales proportionally with the number of organisations. In other words, we risked becoming a victim of our own success the more organisations started to use it, as the administrative task scales linearly the more people come to rely on and use it.

We needed something better.

Enter PlaceCal

As this article so far has probably hinted, our approach to this was going to be different from the usual product-centred approach to software design. Our fieldwork demonstrated that a shared feeling that “there’s nothing to do” stemmed from several sources: a lack of joined-up data sources, technology, staff hours, computing facilities, and resources in general. Through this process we discovered why so many of these kinds of initiatives have struggled in the past, and started to get an idea of the scale of holistic change needed to change that.

Making a community calendar is not a new or novel idea, and many people have tried them before. We realised to succeed, we’d need to let the social needs drive the technical ones, focussing on using technical tools to enable human connections rather than being driven by techno-solutionist imperatives. To quote renowned experimental physicist Ursula Franklin:

Many technological systems, when examined for context and overall design, are basically anti-people. People are seen as sources of problems, while technology is seen as a source of solutions1.

We were determined to change the current product-focused approach to technology, and move towards a system where we enable people to achieve their goals using technology. We realised what we needed to build is a low social capital social network. Social capital is a sociological term referring to the wealth that people have through their social networks: who you know often being more important than what you know. Existing social networks are designed around increasing social capital through the app itself: the barely concealed goal of Twitter and Facebook is to gain followers, who you can then influence. In order to do this, you can spend money on advertising to boost your reach: literally turning economic capital into social capital. Recent news is showing the disastrous effects of this widespread approach to software design, summed up by Zeynep Tufekci as “building a dystopia just to make people click on ads”.

Our goal instead is to encourage real world interaction. We realised we needed to create a site that has as little interaction as possible: where someone could be referred by a library assistant or GP to a social group, make some friends, and never need to use the site again. We needed to create not another place to gain online kudos and trade “likes”, but a tool designed around the imperative of creating a shared understanding of our hyperlocal social spaces. Promoting a big party to a willing audience of socially mobile younger people is very easy using existing tools: finding out how you can talk to your neighbour two doors down at a coffee morning is almost impossible. This design principle ended up having profound effects on the whole process.

Technology as neighbourhood strategy

Our initial findings led to the pretty clear conclusion that neighbourhoods have extremely poor information about themselves. As well as a lack of combined area events listings, there’s a general lack of information sharing within each individual institution in any given area. This is especially prevalent in larger organisations with dozens or hundreds of employees like City Councils, health providers or housing associations which operate top-down systems for publishing polished and well promoted teams that they organise using a top-down structure. These organisations can promote these extremely effectively at these large-scale efforts, but struggle to find out smaller and more poorly resourced activities that are organised by people within their organisations. By contrast, smaller organisations struggle with any promotion at all, relying almost entirely on word of mouth and referrals to engage with local people.

We realised that to succeed, any joined-up source of information must seek to be the de facto information source in an area, that multiple agencies work on together. If we have a single source of information then there are many knock-on benefits: it can be used for social prescribing, as a source for printing out leaflets and posters, as a way to evaluate social isolation and social resources in an area, and a common tool for workers across many organisations to focus on together. In addition it could function as something of a local tourism office, making it easy for local newspapers, radio stations and YouTube channels for example to do weekly or monthly highlights as part of their regular programming.

We put together a successful proposal to gain funding from CityVerve, Manchester’s Smart City Demonstrator project. In contrast to the other Smart City projects in the program that focus on new or emerging product-based technology, we worked with the Health and Social Care strand to create a work programme focused almost entirely on social technology. In other words, how can we overcome the digital divide and enable community organisations to work together to make a great source of information for everyone?

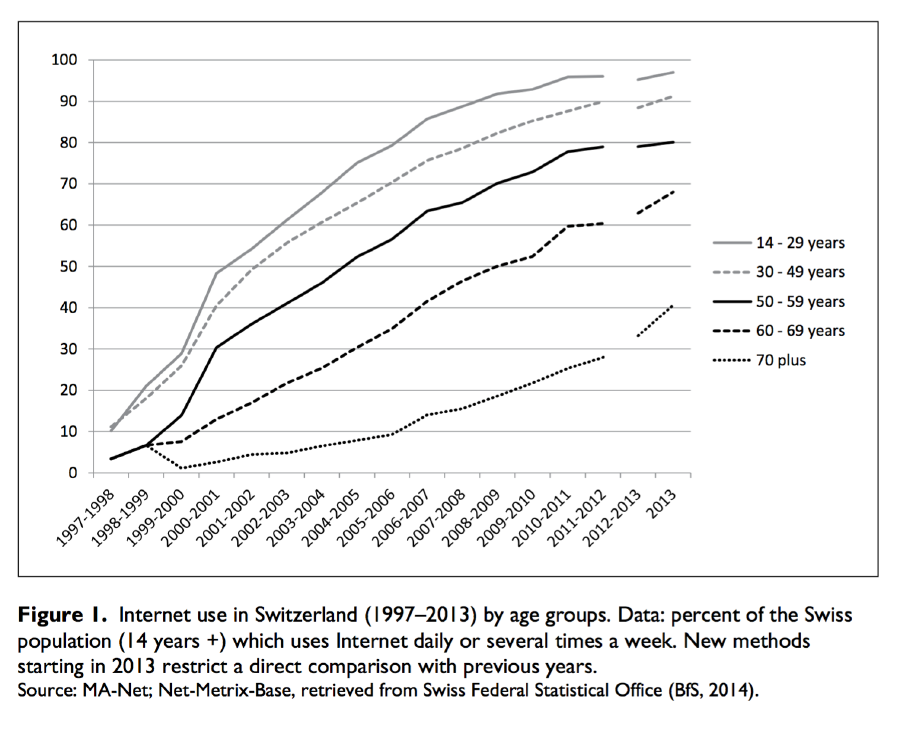

Despite the current focus on high tech solutions, most people’s IT skills are actually very poor, with up to 40% of the working-age population struggling with basic skills like deleting an email. For older people it is likely much, much worse: see the graph below. With a project focusing on older people we knew this was likely to be much, much worse. We currently exist in a bubble where the most technically able 1–5% or so are making apps and websites for a high tech audience, while the average person installs zero new apps a month, for example. We needed a completely different approach — one focused around capability, not products.

A capability-based network

Another name for asset-based community development is the capability approach. It’s used by the UN and World Health Organisation as a methodology for development work both Age Friendly work and their efforts as a whole, and asks a deceptively simple question: what are people able to do? This is the same methodology used for the MAFN project as a whole. One paper summarises the need for this approach as follows:

The deficit-based approach to health tends to focus on health problems, with health-care provision being designed with the aim of solving these problems. An implication of this approach is that communities in and of themselves are not competent to solve their own health problems; rather, health problems and deficits in communities require the expertise of professionals for their solution. (Durie & Wyatt, 2013, sadly not open access)

As we’ve discussed, the capability model states that people already know what they want to do (being experts in their local area), and are unable to due to not having skills, ability or resources to do so. A product-centred approach would be to have a service to do the work of listing information for people: this is how existing statutory service providers tend to operate. Using a capability model, instead we aim to enable everyone to publish their events themselves, eventually not requiring our intervention. The importance of this education-based approach as an axiom of a kind of technological democracy cannot be stressed enough. As noted by sociologist W E B Du Bois: “education is not a prerequisite to political control — political control is the cause of popular education” (1920). Education had to be the cause of PlaceCal: for us, digital inclusion and popular education are one and the same.

In the accessible toilet example given earlier for instance, older people wanted to be able to use health services in their local community centre, but were not able to do so. The health authority wanted to be able to run clinics, but were not able to do so. The partnership together works to help regional providers understand citizens, just as citizens then learnt capabilities to change their social standing.

Returning to the issue at hand: most community organisations struggle with basic web presence, let alone updated events listings. This was a familiar landscape to me from working on Street Support, a platform for services about homelessness. When I was collating the data for the first version of Street Support, the data was coming from all over the place: Facebook pages, broken Wordpress blogs, flyers we found, emails we got forwarded, phone calls. Event information for PlaceCal was no different. Even major providers in the areas who run centres didn’t have the capacity to publish anything past a paper flyer, which didn’t go on their website.

I’m keen to emphasise that given the current landscape, this is quite pragmatic. It’s not a failure of organisations to not publish their activities: on a hyperlocal level, websites are one of the least effective cost/benefit tools. Websites are generally expensive to produce and update, and without a broader platform to plug into they tend to not be very cost effective for organisations with hyperlocal foci. With a target population in a small geographical radius, more traditional forms of promotion like posters, flyers and work of mouth are far more productive and targeted. The core communication problems of organisations making it easy to find out about them and what’s going on are hard to fix, and a website is a crude tool to do so that requires investment and lots of time and training.

We therefore decided to focus on the simplest possible way that people could list event information, and make it our job to publish it. This was to use the software that people are often already using: Facebook, Outlook, Google Calendar, or other similar free or cheap calendar software. All of these platforms as well as the human readable interface have a computer readable feed called an iCal or .ics feed that can be read in by other software. They have stable and mature interfaces that work on a variety of devices, saving us a huge amount of development time to produce. This gives people access to a large range of options, effectively meaning we have several alternate admin frontends out the box, with little development effort.

The platform was therefore designed to be a nexus for these calendar feeds. If we could train someone in each organisation and convince them of the value of maintaining a single canonical source of information using the software they were already using, then we should take that as our starting point and develop our platform to hook into these feeds. This allows organisations to focus on the key competencies of creating public events listings, without having to learn new software.

By doing this we therefore improve capability from both ends. By creating a “fitness landscape” through training and software that drastically lowers the technical capability organisations need to publish events, and simultaneously training organisations in the use of the simplest possible technology, we co-constituted not just software platform but a neighbourhood strategy for information sharing. We think this creates a network of cooperation rather than competition, where the more people contribute to the system the better it works for everyone. The greater the number of organisations that use it, the more it will be taken seriously by local health providers and statutory authorities as the de facto information system for the area, and becomes a canonical source of local knowledge.

Towards a truly open design methodology

This bottom-up design upends the usual product-centred approach in favour of a decentralised one. The Silicon Valley product-based paradigm is like the Beetham Tower, a large towerblock in Manchester. It’s a luxury hotel and apartment complex, with swimming pool, gym, and swanky bar on the 23rd floor. Our internet landscape currently is four or five giant towerblocks like this: the Facebooks, Twitters, and Googles of the world. So predominant is this model of a building, the predominant narrative and structures of tech innovation almost entirely favours tiny 100th scale versions of the Beetham Tower: replete with tiny swimming pools, gyms, and hotels. This vertically integrated model is extremely good for Californian plutocrats backed by billions of dollars of venture capital backing who want to dominate a cultural sector; we suggest that qualitatively and quantitatively different models are needed for genuine social transformation.

By contrast, we aim to move towards a network of people publishing their own data, using low cost and simple methods. It’s akin to building roads into rural areas that are disconnected (without the environmental implications). By focussing on enabling people to control their own information, we drastically improve the overall technological health of an area. PlaceCal is an enabling conduit that works within this new data landscape, rather than being the landscape.

Initial development findings

I’ll write more on the technical implementation at a later date, especially as we’re about to do some heavy restructuring. I’ll leave a few initial revelations that we’re still tackling.

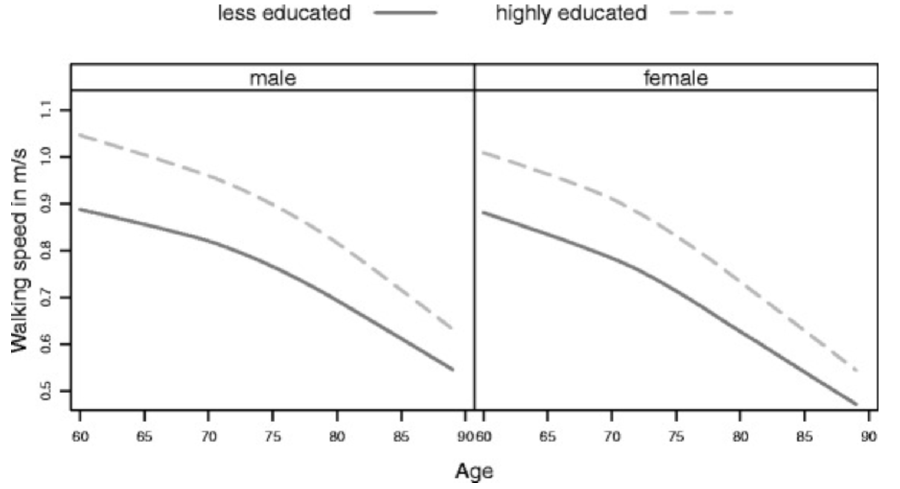

Location data. One major finding was that geolocation was way, way less important than we thought. Who was putting on an event and what venue it were in were far more valuable than quantitative measurements like distance. This makes sense on reflection: people are more likely to go to venues they trust and know how to get to than they are to seek out something further away in an unfamiliar place. Social capital is strongly correlated with the distance you’re willing or able to travel for an event. While people with high social capital go to other countries or cities, let alone the other side of town for an event, most people with mobility issues are often limited to a radius of a few streets around their house. Of course, mobility isn’t the only indicator of social capital, but even within this limited parameter it has a marked effect. The Longitudinal Study of Ageing shows the vast differences in walking speed based on education and age, as well as other factors.

Typology. Our second major observation was that most of these events are not big one-off well promoted and ticketed shows, they are coffee mornings, daily exercise classes, gardening groups and craft sessions. This starts to explain why current platforms like Eventbrite or Facebook are serving these groups so poorly: all major platforms are based around a commercial ticketing and advertising model, not something wanted or needed for the organisations we are working with. This has fundamental knock-on effects for not just the design of the software but the conceptualisation of the platform as a whole: we’re dealing with hundreds of repeating events with little data, not one-offs targeting ticket sales with time and money for promotion. The resources to event ratio are orders of magnitude apart.

I’ll return to the technical implementation at a later date. Overall I’ve been stunned just how significantly the nature of the events and organisations we are hosting has transformed the nature of the entire development process. We did about four months fieldwork before starting any code at all and I’m really glad we did as the insights and complexities of the issue were a long way from where we initially presumed.

Back to where we started then: our launch party!

The Launch: Hulme Winter Lights Switch On

Somehow, through the partnership, we ended up organising the Winter Light Switch On in Hulme Park: and then slowly realised we could use this for the PlaceCal launch as well. We knew we’d never really get anyone to come to a launch for a website other than people who work in the tech sector, but by organising it as part of the winter festivities we had a great chance to demonstrate the website and initiative to residents who might never try it otherwise.

From the start we were set on using PlaceCal as a source of data for flyers and posters, so what better opportunity to pilot it than collating all the Winter parties in Hulme? December is an extremely lonely time for many people, so it seemed self-evident that helping organisations promote their offerings could help people get out and about, and give agency workers a plethora of options to try and get people out to.

In the end, the two-sided leaflet we produced for this was probably one of the most technical jobs I’ve ever been involved in. Through a series of neighbourhood meetings (pictured below) we contacted everyone we knew about their winter offers. Every single data point on the final leaflet came through multiple people and multiple agencies, and had to be reproduced on the PlaceCal website itself. In the end though we created what we’re pretty sure is the most comprehensive winter events listing Hulme has ever seen.

Between us we distributed 10,000 leaflets and posters down the major shopping streets in Hulme and Moss Side, put them through people’s letter boxes, gave them to parents at schools, and generally plastered the area. By now you’re probably getting the point that by making one really good source of information together, we multiplied our capacity and reach. Through this process we had loads of conversations with local shops and businesses, made some more connections, and got some great feedback. We’re looking forward to being able to go back and see how people got on!

The event itself was a huge success with hundreds of people coming throughout the day. Over the course of the day we had carols from local schools in the park, live music, the One Manchester bus, a fire engine with a snow machine, loads of food from local organisations, mosques and churches, and of course the PlaceCal demonstrations which nearly got lost in the festivities! We also got to line up with Z Arts current production for people who wanted somewhere to go afterwards. The highlight for me was wondering why it had got quiet for a bit, before realising the imitable DJ Lord Kemoy Walker had a dancefloor full of kids dancing to Gangnam Style just before wrapup!

I hope this article has given you an insight into not just the PlaceCal design process, but what we hope is the groundwork for a more connected way of delivering technology in a community context. In future pieces I’ll cover what we have planned for PlaceCal in 2018, and document this methodology that we’re calling Community Technology Partnerships. As it happens, we’re also starting a bus service…

If you want to keep up to date then you can follow us here, on Twitter or Facebook. If you’re an organisation looking to get involved in the platform, or a neighbourhood partnership, health provider or local authority who would like to have a chat with us about rolling our PlaceCal in your area, don’t hesitate to contact us by email: support@placecal.org. The PlaceCal design and illustration is by the awesome Squid.

-

Ursula M. Franklin’s (1989) CBC Massey Lectures, “The Real World of Technology” ↩︎

-

“The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors” (Friemel, 2016) ↩︎

-

“Men’s and Women’s age trajectories of walking speed by educational subpopulations” (Weber, 2016) ↩︎