Blog

Manchester Community Histories in the Shadow of Urban Regeneration

A report on our community history day in November 2019

On a chilly Saturday morning last November I joined other local residents, activists and researchers to participate in the first Hulme & Greenheys Community History Day in Manchester. The event was held in the historic Old Abbey Taphouse, one of the few nineteenth-century institutions to have survived the multiple waves of state-led ‘urban regeneration’ that have irrevocably transformed the area over the past sixty years. Organised by the pub’s co-director Rachele Evaroa in partnership with Kim Foale, founder of local tech enterprise Geeks for Social Change, the day’s activities were designed to bring people together to share firsthand accounts of life in the old neighbourhood as well as foster dialogue about the impact of city planning and urban regeneration initiatives on local communities – then and now.

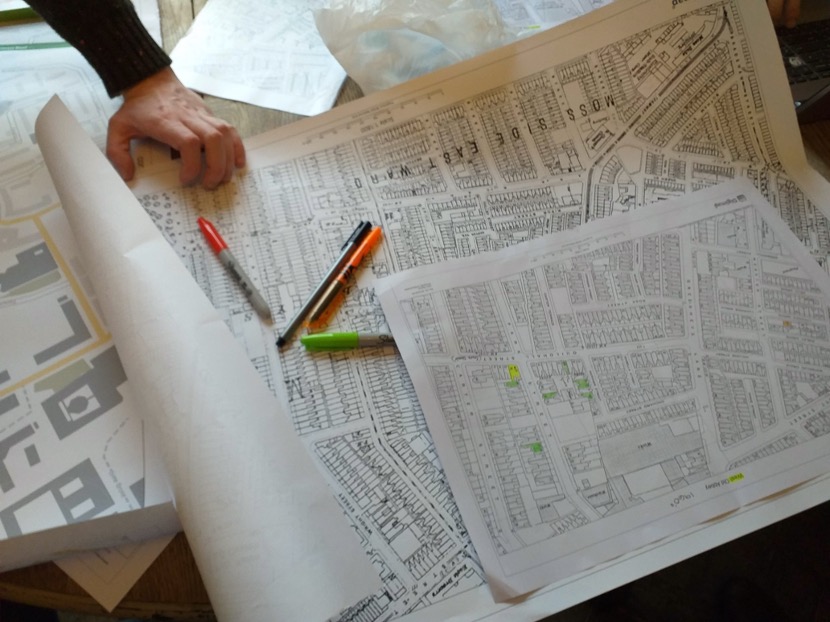

Upon entering the pub, I was greeted by the sight of former residents grouped around tables, sipping cups of tea and sharing stories. Others were huddled around a long table covered with historical maps, each taking the opportunity to point out cherished sites long since destroyed and built over.

As a researcher at the University of Manchester, I was fascinated to trace the contours of the bustling multi-ethnic working-class communities that had once occupied the streets immediately behind the South Campus in what is now known as Manchester Science Park. My own research over the past year has focused on the historic battles waged by residents of that neighborhood as well as nearby Moss Side to stop the bulldozers from moving in during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

After WWII, more than half of the city’s housing stock was deemed ‘unfit for human habitation’ and in dire need of redevelopment. The Victorian terraces of Moss Side, Hulme, and Greenheys emerged as a key focal point with city authorities announcing plans for large-scale ‘slum clearance’ in 1967.1 It is important to recognise that these neighbourhoods had served as an important ‘gateway’ for migrant workers beginning with the Irish during the late nineteenth century and followed by early African seamen as well as subsequent postwar ‘New Commonwealth’ migrants from the Caribbean and Indian subcontinent.2 By the mid 1960s, 60% of all Caribbean migrants to Manchester lived in Moss Side – a spatial configuration reinforced by extended kinship networks and unchecked discrimination in the housing and banking sectors.

This ‘color bar’ also extended into many public accommodations including the Old Abbey Taphouse, the publican of which famously refused to serve local boxer and activist Len Johnson, spurring a series of ‘drink-ins’ in 1953. Despite these barriers, many residents managed to purchase homes and started their own businesses including the many clubs, restaurants, and grocery stores that dotted Denmark Road.

Against this backdrop it is unsurprising that residents organized to resist top-down urban regeneration schemes and forced relocation. To learn more about these campaigns I visited the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre, which preserves rich archives related to Manchester’s multiethnic communities. Among them are the papers of Guyana-born activist Elouise Edwards whose home was located in the heart of the demolition zone at 78 Platt Street. Residents, including Edwards and her partner Beresford Edwards, came together to form the Moss Side People’s Association and it’s subsidiary Housing Action Group, which held regular meetings, staged demonstrations, and published an independent zine called Moss Side News. The group aimed to inject residents into the planning process and ensure that they had a voice in the future development of these communities.

As our contemporary urban landscape makes clear, local activists were not successful in halting demolition. Between 1970 and 1974, the bulldozers moved in and gradually forced residents and most business owners out. Elouise and Beresford Edwards were among the final holdouts; their house was the last one left on the block when they departed in 1974. At the Community History Day we got to hear the personal stories of several former residents and – with the support of archaeological technician John Piprani and his team – used Digimap and GPS technology to identify the exact locations of the homes in which they grew up. John Piprani has written a blog on this process which has more photos and thoughts from the day.

After lunch, we returned for a series of workshops organized by residents, cultural practitioners, and community historians all engaged in vital heritage-making practices related to the area. Through family memoirs and photobooks, theatrical performances, and oral accounts we are all constructing histories capable of outlasting the bulldozers and, hopefully, shaping future discussions about the impact of urban regeneration in our communities.

Dr Kerry Pimblott is a Lecturer in International History at Manchester University. You can follow her on Twitter @DrPimblott and read more about her project Race, Roots & Resistance.

-

To learn more about Manchester’s urban regeneration projects of the 1960s and 1970s, see, Peter Shapely, The Politics of Housing: Power, Consumers and Urban Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007). ↩︎

-

Laurence Brown and Niall Cunningham, ‘The Inner Geographies of a Migrant Gateway: Mapping the Built Environment and the Dynamics of Caribbean Mobility in Manchester, 1951-2011’, Social Science History 40:1 (Spring 2016): 93-120. ↩︎