Blog

Everything is connected, but should it be?

What if storing user data at all is a dark pattern?

Content note: This article contains discussions of classism, police brutality, incarceration, sexism & misogyny, forced deportation and racism, with brief mentions of rape, violence, blood & needles, death and genocide.1

“Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence” - Article 8, European Convention on Human Rights (1998)

I have worked as a software developer for twenty years. In my lifetime I have seen the internet go from a utopian dream of connected knowledge to a dystopian surveillance network overseen by global superpowers.

When I started my career, computers were primarily seen as standalone entities: robot butlers (fig. 1) for the technologically privileged (as opposed to the robot symbiotes, or parasites, that we now keep in our homes and our pockets). The robot could only see what it was presented by its human owner. It could not yet read our thoughts or desires, eavesdrop on what we said to our friends and lovers in secret. And if it could, well, it was only a subtle interference. Polite.

Circles of tech counterculture foresaw the issue that privacy would become. But for most people, including the burgeoning industry growing in California, it made sense to dismiss any such concerns as low priority, something to be fixed ‘down the line’.

But in the space of just fifteen years, routine mining of data from individuals has become a major cog of the global economy and national security apparatus. Hyper-networked robots not only know far more about our lives than we have offered consensually, but they also have gigabytes of data on us that we don’t even know about ourselves. They feed data to and ingest data from other machines, services, and agencies frequently and minutely: high frequency trading for personal information. This gathering and sowing is second nature to them. This data is then correlated and synthesised by silent overseers with a vested interest in the mass gathering of personal information to be sold to the highest bidder. This system, as it is, has played a dominant role in international geopolitics and will continue to have catastrophic consequences.

Current privacy discussions tend to focus on what are, in my view, trivia of this current state of affairs. Decisions about privacy mainly happen only within the ‘chrome tower2’ of technology production. If they are considered at all, issues of privacy are designed solely around how they affect the presumed core demographic for the technology – i.e. WEIRD (Western, Educated, from Industrial, Rich and Democratic countries), white, straight, cisgender, able-bodied men.

It’s easy to find examples for this type of thinking even on the most surface of levels: smartphones becoming too large to be comfortably held by any but the largest of hands; automatic hand dryers whose sensors fail to register darker skin; and Apple releasing a health app claiming to cater for ‘your whole health picture’ but neglecting to include the simplest of provisions for half the world’s population, a period tracker.

What the people behind these innovations do not care about are the radical differences in how privacy affects people differently based on their social capital. This means that even people with ‘good intentions’ end up designing socially damaging software because they wilfully neglect to think about implications that don’t affect them personally. These are people who are never (or rarely) affected by the negative consequences of privacy fuckups. The worst case scenario for this demographic is having to change their password every now and then, or being the victim of easily rectified credit card fraud.

For the citizens of Myanmar, the military’s abuse of privacy, enabled by Facebook, was used to incite genocide. Needless to say, Facebook’s Head of Security at the time still has his job.

Between these extremes, and especially on a more local level, the impact of vampiric (predatory, extractive) privacy policy can be harder to see. I’ve become personally entangled with it in a few different ways, initially by the very fact of being an activist who also happens to be queer, trans and disabled in addition to being a software developer and researcher.

Most recently, the work of Resistance Lab, an anti-racist collective who aim to find new ways to resist state violence, in Manchester has cemented something for me: that the dream of utopian connectivity we were promised could not be further from our current reality.

Living in the Manchester surveillance state, case studies

In Manchester, where I live, Black people are eight times more likely to be ‘stop and search’-ed by the police, according to official stats3, which we suspect is an underrepresentation of the true figure. In practise this happens when ‘stop and search’ efforts are focused on ‘problem areas’ (read: Black areas) such as Moss Side, where, for example, one person was searched 16 times. The results of these efforts produce an ongoing supply of minor offences that are then used to justify further over policing of these areas – a self-fulfilling prophecy. Meanwhile, ‘white collar’ crime in nearby financial districts such as Spinningfields is completely ignored and therefore has no evidence base.

Under ‘joint enterprise’ legislation designed to make, say, the getaway driver of a bank robbery equally liable for crimes taking place during the robbery, 11 young people from Moss Side were sent to jail for one murder. The evidence for their connection? Smartphone footage of ‘gang signs’ being made, taken at a youth work session in a building that contains the local library. The gang sign? An extended middle finger. This is not an isolated case. The ethnicity and social class of those convicted will surprise no one.

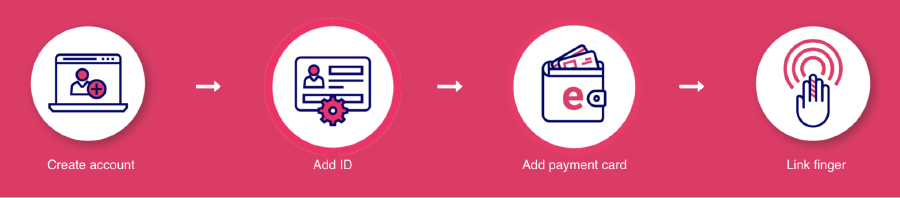

The Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham now plans to put police officers in schools4, despite large coordinated public efforts and independent research by campaigners. So when he also says he wants to start tracking people’s fingerprints and veins in order to use the tram, it’s hard to imagine that this data won’t be used in the most totalitarian ways.

How do technologies like ‘VeinID’, which is essentially straight out of 1997 sci-fi film Gattaca (starring Ethan Hawke, Jude Law and Uma Thurman), end up not being dismissed as dystopian movie plots, but given regional working groups and financial incentives to operate? The simple answer: because the people in the chrome tower – developers, funders, politicians, tech evangelists and financiers – are usually in the tiny minority laid out in the introduction. To them, this is a simple financial convenience that means you don’t need to take your phone or card out your pocket to pay.

For others in Manchester this couldn’t be further from their reality. Is it too hard to imagine that the next ‘joint enterprise’ arrests could be based on data of multiple people who happened to board the same bus? Does it seem unlikely that Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) teams would match fingerprints taken at Dallas Court Immigration Centre (where asylum seekers and refugees must regularly report) to those taken by city homeless services, and used as grounds for deportation?

What we are learning is that one person’s convenience can easily result in another person’s imprisonment, deportation, or death.

If this all sounds too dystopian for you, the NHS have already shared supposedly anonymous ‘track and trace’ data with the police in a massive breach of patient confidentiality. Right now, the Undercover Policing Enquiry is investigating decades of abuse by officers against innocent members of the public, including multiple women deceived into long term sexual relationships with police officers – they consider this rape (I do too). Their reporting went as far as to keep records of the profits made from bake sales by women’s groups; at a social centre cafe I used to help run in Leeds, what we assumed to be a series of money handling errors was almost certainly deliberate sabotage by an undercover police officer. We must stop seeing these events not in isolation, but as part of a consciously constructed element of the global military-industrial complex.

A practical example: the different types of user account

So far I’ve been talking ‘big picture’ about the national and international implications of neoliberal approaches to privacy. To better illustrate how these large and connected systems affect the most vulnerable in even the most innocuous ways, I’ll analyse one of the most commonplace acts we do online today: creating an account. This is a step that happens almost imperceptibly in our online lives nowadays5, especially through ‘login with Google or Facebook’ functionality.

Broadly speaking, four kinds of accounts come to mind:

- “Consensual”6 accounts, where we optionally sign up to a service we want to access, usually clicking some ‘I agree to the terms and conditions’ box that we never actually read (at least without dedicating 76 days a year to it).

- “Semi-consensual” accounts, where creating an account is mandatory for say, a job or residency status, but we would really rather not have one7.

- Non-consensual accounts, where data is stored on us by the police or security services against our will.

- Non-consensual “anonymous” accounts, where we are tracked by a variety of device identifiers that means ads can uniquely track us through a range of means.

Privacy discussions almost always centre the first type. We consent to signing up to a desirable app or website. We type in our email address. We conduct interactions within the app; as a casual user there are no third party ways you can access Facebook except for through the application itself, for example. By design, we are made to think of these as ‘vertically integrated’ closed gardens, a set of separate ‘data buckets’ that don’t cross over.

The infamous Cambridge Analytica leaks showed that even in this first and most preferable case instance, it is not possible to know what we are consenting to: namely, the wholesale connection and farming of all data we have ever published online, in all four categories, using both legal and non-legal methods. I suspect nobody who had their data extracted from Facebook, and then linked with hundreds of other sources to create materials for the use of ‘dark arts’ political consultants, would have consented to this if given the option. And yet despite the scale and severity of the crimes, no one has gone to prison for this scandal. Only a few small financial penalties were handed out. Doubtless there already exist legions of Cambridge Analytica clones we have yet to hear of, and every nation’s spy agency has some version of the same information.

That is the most well-known example of what I’m talking about. But every week there seems to be another huge leak from another big website or third party processing service. These range from the Ashley Madison leak of people seeking extra-marital affairs, to banking information on over a billion individuals, to the DNA data of individuals collected by companies who sell genealogy kits. This datavis has a partial list.

Each of these leaks is bad enough as it is. With a simple search key (e.g. email address), they can all be interlinked, giving anyone with the money to access it the ability to surveil individuals to an order of magnitude never before possible in human history. This data can then be stored in perpetuity. While GDPR has provided at least some theoretical restriction, it’s impossible to imagine that these companies will do anything differently, especially given the fines levied for data breaches will almost never outweigh the financial benefits gained.

In this context, privacy is incredibly relative. Much as the average British person apparently breaks the law an average of 32 times a year and never gets arrested, most of us are constantly having our privacy violated and will see few direct consequences. However, both the direct consequences to those that the state or private sector sees as a threat, and the indirect consequences for civil society as a whole, cannot be underestimated.

What if logins and user accounts themselves are the problem?

In my opinion one of the only remaining websites in daily use that lives up to that earlier utopian vision for the web I mentioned at the start is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is not only free, but it doesn’t need a login, and only tracks your IP in order to ban ‘trolls’. Of course, you can login to Wikipedia if you want credit for your edits or to join the wider Wikipedia community – the vast majority of users do not.

This is, of course, anathema to the current way apps are developed. It’s hard to remember the last significant project that operated under a similar guise.

‘Uber, but for X’ has become the most typical flavour of pitch, to the extent it has become the easiest joke to make in tech circles. It’s worth noting that Uber is one of the most toxic companies on Earth, whose stated plan to be profitable requires all of the world’s transport to be replaced by Uber, and all the drivers replaced by AIs. Uber simply wouldn’t exist without extreme surveillance of not just drivers and customers, but also ‘problematic’ lawmakers and city officials to help avoid being caught breaking the law. Nevertheless, the model is frequently held up as some kind of ‘gold standard’ of app quality.

‘Sign up’ and ‘maybe later’, like two options that a pushy guy at a nightclub trying to get you to go home with him might present to you, are now the default dark pattern for many websites. Many of us will have had “you didn’t complete your order” adverts that seem to inexplicably follow us from site to site – proof to even the casual user that the websites they visit are not self-contained units.

Why do they push this? Because getting people to create a user account has inherent value. This is the inevitable consequence of a common marketing methodology called the ‘AAARRR Funnel’ (or ‘Pirate Funnel’). This acronym stands for ‘Awareness, Acquisition, Activation, Retention, Referral, Revenue’, each letter referring to a stage of the process of making a purchase or registering for a service. To implement this methodology, you first need the ability to track each aspect of this - from that first browser cookie, to account creation, to a login, to a re-login, to inviting your friends to join, to making a purchase, a repeat purchase, and so on. I have no doubt this works - as with most marketing tricks, this is the methodology half the web is based on, and why examples like the ones below are becoming more frequent every day.

I cannot begin to describe the rabid fervour that everyone from business executives to so-called ‘data evangelists’ to public sector managers have nowadays for gathering as much data as they possibly can – petabytes of it to be stored in a data lake, data warehouse, or other such metaphoric term. Often this literally happens in the same breath as discussions of privacy, data ethics, open source, or other in-vogue tech concept. Suggestions I’ve made to have even basic citizen oversight of data collection of Greater Manchester-wide data gathering initiatives have fallen on deaf ears. Somehow it has been widely accepted that the more data you have the better, as if data is a countable resource like money, and that if you just have a lot of it, good things are bound to happen, and that whatever risk this creates is worth it despite the fact we can’t articulate the benefits just yet.

In the desire to see data as the new oil, these people have either forgotten or simply don’t care that, much like oil, data generation is an extractive process designed to make a profit (or a comparative cost saving) for the owner of the data, and it is, much like with oil, apparently worth trampling over basic human rights, national sovereignty, and the environment to get. Despite the (ironic?) complete lack of evidence for it, we are told this will have health and wellbeing implications too. Maybe there is, but never is this done as a cost/benefit analysis – at least, I have never seen the risks seriously evaluated on any project.

Most software is information software

Interaction designer Brett Victor (2006) defines three kinds of software: information software, manipulation software, and communication software. Information software is where you want to find something out (Wikipedia). Manipulation software is where you want to make something (Word, Photoshop). Communications software is where you want to communicate with someone else (Email, WhatsApp).

Most software is information software. Most of the time, we want to just find something out or browse. And yet, interactivity is all too often pathologically shoehorned in. All of the major platforms – Twitter, Facebook, Instagram – continue to make their apps more complicated, merging so many features into one package until these platforms become more and more indistinguishable from each other. This is because backers correlate increased interactions with increased profit as per the Pirate Funnel.

The software industry is obsessed with it. Keep in mind that this software industry is the same one giving us Facebooks and Ubers, software the majority of us now use begrudgingly or with vague resentment. Maybe… we shouldn’t listen to them?

I maintain the simple position that apps should not even have a login unless there is an incredibly compelling reason. It just so happens that not only does it make things easier to use for 98% of users, but also that the sites end up working better for everyone as a result.

Even software that is explicitly designed to help vulnerable people often falls into the same traps laid and monetised by the chrome tower. Without being too specific, I’ve seen too many cases of concepts such as ‘Amazon, but for foodbanks’ getting financial backing from tech business accelerator schemes, where investors can see there is potential money to be made from desperate volunteers looking for resources and help in coordinating services. In these cases, the invasiveness of their techniques and disregard for the sanctity of privacy is only drawn into even more sharper focus by their explicit aim to safeguard and protect.

Street Support, a directory of homeless services that I worked on, does not require a login for the majority of users. There is endless pressure placed on all homeless services to track and monitor homeless people using their services. We put our foot down and said no. The people this directory was for tend to have intermittent internet access, usually in libraries and homeless centres, which meant that requiring a login could have actively harmed people in two ways: by making it more difficult for them to find information on crucial life-saving services, and by opening up their data to be captured by the government, therefore putting them at danger of deportation and more. Instead, two data points – what area you want to find out about and what kind of service you are looking for – were more than enough for our users to find relevant information. This had the knock-on effect of making the service widely useful for a large range of stakeholders and to have the results rank highly in internet searches.

While I was writing this piece, I got an Instagram ad which perfectly captures the more orthodox position of modern startup design (see below). This app actively encourages people to go around taking photographs of homeless people and uploading them to their server, where we can see their name and balance. Before even getting into the root causes of homelessness and what is actually needed in the sector (hint: houses), homelessness, as I have already mentioned, is now grounds for deportation. It only takes a second to realise the harm that could be caused by this initiative. While seemingly extreme, this is not unlike dozens of other ideas I’ve heard in ‘tech for good’ circles.

But what about when we do need a wider range of people to upload information?

I don’t claim to have the solutions to all of the problems I’ve touched on so far, and I certainly don’t have the social capital or the ‘capital’ capital to enact any of them globally, but I do at least try to put my money where my mouth is (so to speak) and think very carefully about design around privacy in projects.

My current flagship project, PlaceCal, is a website for neighbourhoods based around a shared community calendar and underpinned by the coordination of mutual aid in neighbourhoods8. I designed the software to build on top of the software people were already using: Google Calendar, Facebook, Outlook. All of the data we collate is public data about services pulled in (by the PlaceCal software) from public share links of existing services. That information, though public, is still only collated with the consent of the owner. The initiative as a whole was co-produced with Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods (MAFN), a resident-led multi-stakeholder partnership of people working to make the city better for the over 50s.

Then, how do we decide who can add information? PlaceCal’s methodology is to work with a trusted community organization in each area who then onboards other community organisations – in other words, everyone publishing data is explicitly whitelisted via existing real life trust networks. In this instance, those links were established in the MAFN partnership. We wanted people to go to events in real life, so we didn’t include anything like a comment system (with its associated moderation headache). Instead we used our resources to focus on ‘big picture’ digital inclusion issues.

By design, the ‘end users’ of both PlaceCal and Street Support are anonymous. Nothing is gathered about our users. We simply do not store data on them. To ensure we are meeting the needs of our target audience we simply ask them.

Instead of asking people to register an account, enter their details and select areas of interest, we get all the context we need from the website focus itself (homelessless, age friendly activities) and the ward they want to see results for (most people want to go somewhere familiar and local). These two datapoints were more than enough to give useful and relevant results. The focus of our efforts therefore became making sure that the service listings were complete through community engagement, rather than obsessing over the details of user profiles and logins and creating ‘achievements’ and push notifications in the app.

In PlaceCal’s case, people can find (and do find, when we aren’t in a pandemic) a weekly event near their home that they previously didn’t know existed, go to the event, establish a real-world connection, and maybe never check the site again. In some cases it was their GP who referred them, so they didn’t even touch the site directly. (It’s hard to overstate how much public health practitioners simply do not have easily searchable simple text databases of local health services available to them). Similarly, in Street Support’s case, we have absolutely no data on how it helps homeless people (or not).

So how are we to know it works if we don’t siphon off every drop of data we could possibly gather into a private data lake for analysis by a third party? Because we trust the people we talk to about it to tell us it works, through ongoing engagement with our project partners. We get constant feedback from community development workers that their work would be impossible without it – and in fact,_ is _impossible in areas without these interventions.

So why aren’t more sites like this? The simple answer is that this logic goes down like a lead balloon with funders, for whom their only model is a case-by-case basis, who want a graph or preferably a pretty infographic showing a line of ‘goodness’ going up. Big institutions are currently investing serious sums in community engagement and investment funds, writing about communities in their marketing materials, and promising ‘people first’ or ‘citizen led’ approaches.

But when push comes to shove (which it always does), interventions which create cold hard receipts of every small interaction win out every time over those that do sensitive work creating long term change. At the coalface, well regarded potentially life saving peer-led local services are canned every week. Commissioners and funders want you to make people a cup of tea, but only if you get their postcode and take a picture of them for evidence, or how else would you know that your hot drink fund is reaching those who need it most?

A refusal to take part in this process for the dignity of your service users is a Sisyphean task. I have spoken to dozens of practitioners who have experienced this and privately share this view but are unable to talk about it publically for fear of being financially cast adrift, and dozens of funders who want to “yes, but” me into a corner until I give up. It sucks.

I think this, very simply, stems from the unconsciously adopted view both within and without the chrome tower that the Pirate Funnel is basically a good thing and is the only ‘true’ way to monitor a service and demonstrate ‘impact’. Decades of indoctrination by billion dollar corporations has seemingly convinced middle managers with Fitbits and Alexa-controlled lightbulbs everywhere that they must be on to something, and somehow a methodology designed to sell Nespresso subscriptions or Call of Duty loot crates must also be applicable to public services.

Silicon Valley firms spend a whole lot of money promoting that some of the most immoral people in the world today are maverick t-shirt-wearing inventors worthy of idolisation, and not frenzied capitalists funded by billions of high risk investment capital overseeing the most efficient transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in history. We even create superheroes based on their archetype. Is it any wonder that people believe they must be doing something right?

Conclusion (of doom?)

Does your new app truly need users to create an account, or can you just give the information away for free? Do you really need to ask the ethnicity of your event participants, or can you just look around the room and see you have inclusion work to do without demanding the people affected the most by this provide receipts? If you gather information on the gender status of employees, how are you going to guarantee this doesn’t fall into the hands of the Daily Mail?

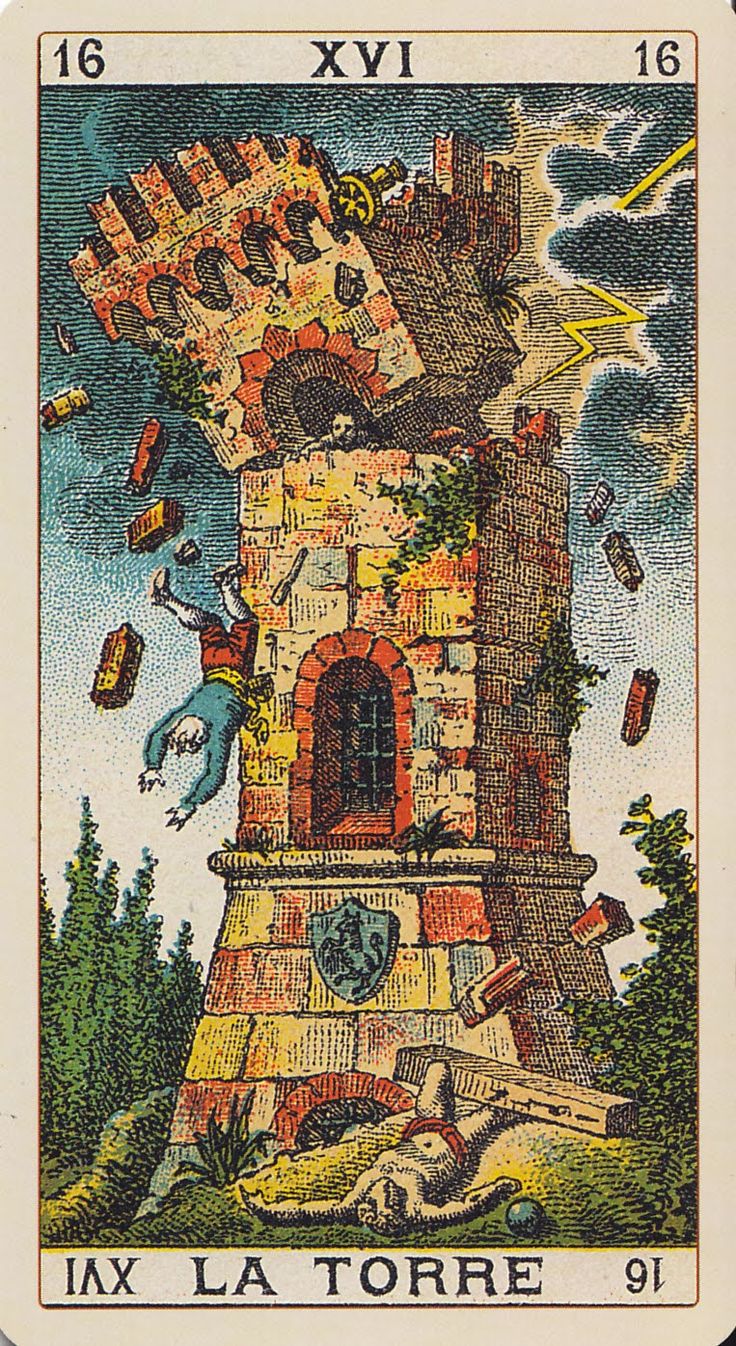

Maybe you truly do need those things. Or maybe the parasitic desire for more data at any cost should be called out for what it is, a fascistic tendency with dire consequences. If we continue churning out softwares and technologies without fundamentally changing how we treat privacy and how we regard users, we will simply be building the final floors of a structure not unlike The Tower, a tarot card from the Major Arcana, which depicts a gigantic high rise built on shaky foundations. Like The Tower, which signifies chaos but also revelation, maybe the crumbling of the tech industry (and those who fund it) from the ground up will be a necessary, and welcome, revelation that will herald a new age. But should we always need prophecies of such apocalyptic scale to come to fruition before we can incite change?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to co-author Jazz Chatfield for his significant contributions to this piece, Beck Michalak for the venus fly trap illustration, and Natalie Ashton for inviting me to write this for the Norms for the New Public Sphere project.

-

This list does not include warnings for the content of linked news articles, so please view at your discretion. I have tried to make this list as exhaustive as possible, so please let me know if there are any I have missed. ↩︎

-

Academia is often referred to as the ‘ivory tower’ due to its lack of accountability and disconnection from the rest of public life. I’m coining this term to refer to the same phenomenon in the tech industry, as discussions increasingly only centre the voices of developers, ‘tech evangelists’ and financiers, and not wider society. ↩︎

-

It’s worth pointing out that GMP have been placed in ‘special measures’ and the Chief Constable has resigned over their data gathering and publishing practice, so all their statistics are currently under suspicion. ↩︎

-

Currently on hold due to Covid-19. ↩︎

-

For older and disabled people this can of course be an insurmountable barrier and one of the biggest barriers to digital inclusion, but this will have to be a discussion for another time. ↩︎

-

Placed in “scarequotes” because often creating an account is a mandatory step that is hidden at the outset. ↩︎

-

Protip: if you need a temporary email address to activate an account you can use browser-based tool Tempail. ↩︎

-

For more on this, check our journal article about the application of the capability approach to IT production in an inner-city neighbourhood in Manchester. ↩︎