Blog

Technology isn't a magic wand, it's a treasure map.

...And you still need the right team to get you to that red X.

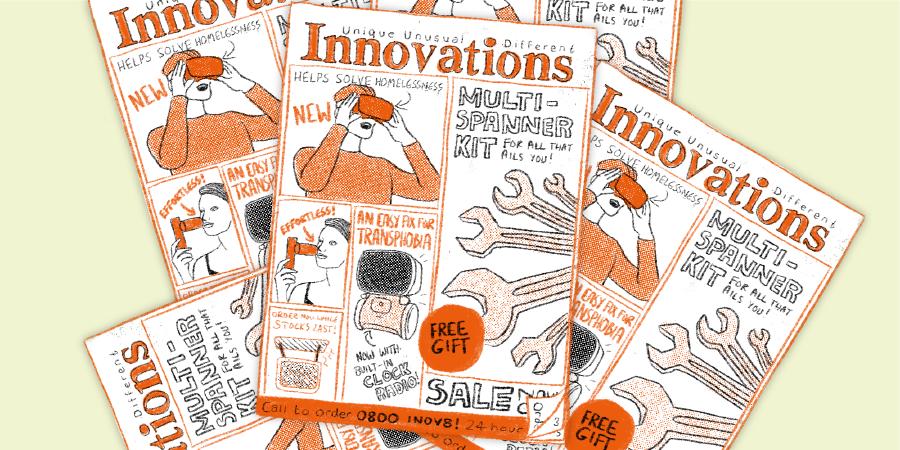

I used to love the Innovations catalogue dropping through the door with the weekend paper. For an entertainment-starved tween, it was a mix of ludicrosity and earnestness that made for ideal Sunday browsing.

This was a simpler time for home technology, a time before the realisation of Bill Gates’ “a computer on every desk and in every home”. Family PCs were big clunky things that lived in the “computer room”, a room certain family members would loudly make a point of avoiding.

Computers were stand alone curiosities, a device to play Solitaire on or type up notes, something more akin to a woodworking workshop in the basement than to the hyperconnected always-on communication platform-from-hell it’s become today.

If permitted to take up space in a more general-purpose living room, they would hulk alienly from the shadows of a “computer desk”, a blinking monolith from the future.

Innovations gave a spotlight to niche ‘inventions’ that aimed to solve mundane problems with over-the-top gadgetry. Palm pilots and calculator watches and clock radio toilet roll holders. (Everything had a clock radio.)

These things were often laughable, and I think that was the point. They were just fun sounding things, things you don’t know how you’d lived without until now, things that didn’t actually solve any real problems anyone had.

It fitted in that gap between “I need that!” and “But do I really?”, the gap that is probably responsible for killing off the catalogue in the pre-online era, with its built-in cooling-off period during the time it took to mail in a form or call a phone operator.

But a lot of inventions of this era were seemingly designed to fit in this Innovations sized-hole. The promise that all of society’s smallest problems could be improved by upscaling your toaster was an intoxicating one.

Move on a bit, to the present day, and Amazon is the world’s Innovations catalogue.

Many of the sales models used by startup tech businesses are based on this direct mail marketing approach. This includes Russell Brunson’s hugely influential “Dotcom Secrets: The Underground Playbook for Growing Your Company Online”, a book partially responsible for almost every irritating online sales trick you see today, and others like it such as Eric Ries’ “The Lean Startup”.

These approaches, combined, outline a methodology for making products in a distinctly Innovations-y way: Find a tiny thing that people might want. Build a product that promises to fill the gap. And price it so that it seems impossible to refuse.

Do people actually need it? Or does it accelerate our planet further towards destruction while doing nothing to fix any real problems? Who fucking cares. It’s innovation, so therefore morally neutral, or even by default good. Everyone loves innovation! Who doesn’t love innovation? Don’t you know what innovation has done for you, personally? Look at what we can do!

This idea is been so persistent that it’s the only real concept most people have of what technology is. It’s a thing, a device, a service, an app. Something that sort of fixes a problem you have. At least in part, at least sometimes. It’s a piece of glittering promise shorn from its creator, a discrete offering that doesn’t visibly need a human interaction or connection. Or maybe just a piece to a bureaucratic puzzle that manages your life admin.

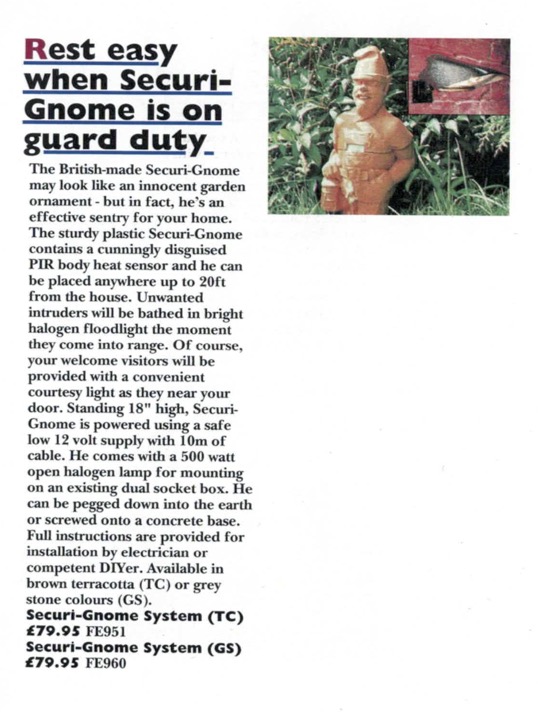

Due to the massive amounts of money and hubris that reside in the tech sector, we now seem to believe that the same methodology used to sell pens that write upside down with a built-in dictaphone can somehow be adapted to fixing homelessness, or poverty or something.

Sorry, but I’m here to tell you this isn’t a thing.

Fixing difficult social problems, or any problems other than the utterly trivial, is (as the saying goes) a journey not a destination. Hard problems are fixed with hard work, or they wouldn’t be hard. And yet there is no shortage of snake oil salesmen telling you the opposite, that somehow you can undo decades of racism, transphobia, poverty, or whatever other issue with a nice app or a bit of data or a subscription to our service.

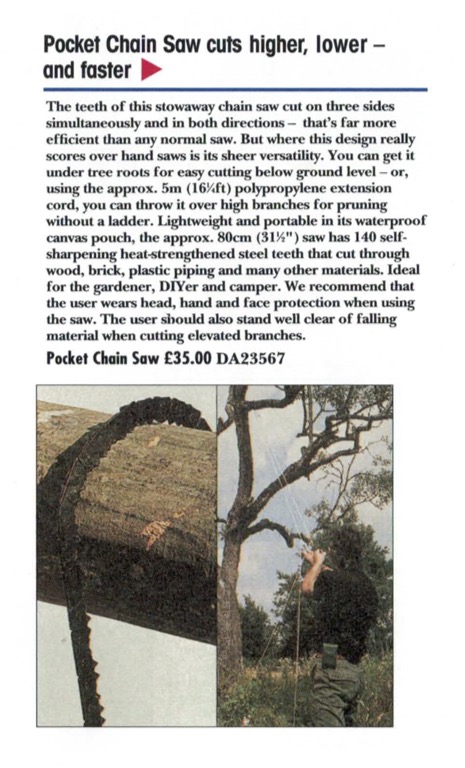

People expect tech to be a magic wand: wave it and fix a problem. But for any serious problem, this doesn’t work. In the same way owning a set of spanners doesn’t automatically make you a car mechanic, much less able to run a garage. And yet, policymakers seem to think all they have to do is buy spanners (with dictaphones and clock radios built in of course) and somehow the cars will get fixed by magic.

The worst part is that this is now the world those of us engaged in on-the-ground communities and mutual aid groups have to deal with. We’re seeing a wave of people come in who just want to fix things with Design Thinking or Human Centred Design, and their new set of Internet of Things-enabled spanners.

People who inevitably lose interest when they realise they can’t just design these things away, and that communities don’t actually have any loose bolts we can’t tighten ourselves, we just don’t have the time or resources to tighten them. Or worse, they hit on a way to extract money from these communities, and become very successful from it.

On the community level, we are always dealing with gnarly problems — problems that are eminently fixable by a great team and with a good plan. Devices are secondary.

Imagine you’re planning an archeological excavation. Nicer gadgets are helpful, sure, but you’d also need a team who knows how to use them.

Archaeology changes slowly over time as new technology facilitates advances in the field. But the core work of excavating a dig site doesn’t. That is the technology.

With all the lasers and 3D printers in the world, you still need a team of people with trowels and brushes who know what they’re doing. And you always will.

Acknowledgements

Words by Dr Kim Foale. Literary spice and Nicolas Cage content by Jazz Chatfield. Illustration by Emma Charleston.

-

Nick Biggs, Innovations Catalogue, 2004 ISBN-13 978-0747573463. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Obviously, this isn’t a real listing, but it fooled Kim until the third read-through. From National Treasure (2004). ↩︎